Presentation of the Polish poster.

Poland in the 80s

Photo Wikicommons - Roman Naumov

created for the inauguration of the Palace of Culture and Science on July 22, 1955.

Over forty years ago, the implosion of communism in Eastern Europe surprised everyone, from the man in the street to political leaders.

While the manipulation of information in communist countries was a rule, if not a habit, we, for our part, were subjected to information that caricatured regimes subservient to Moscow, "the evil empire," as Reagan called it in his time, reducing them to a series of clichés, basic and often inaccurate... that hasn't changed!

Strangely, after the disappearance of the Communism, these clichés die hard, and I have the impression that history tinkers with the truth a little. One of these clichés was that art responded to directives issued by the Party, and had to follow a defined and controlled aesthetic line. The reality could be very different depending on the country.

Regarding Poland, it is perhaps worth knowing that this country was wiped off the map for over 150 years, carved up by Germany and Russia, surviving only through its culture, language, and religion.

Photo: © Pascal Piskiewicz

for "Rayonnement de la paternité," a play by Karol Wojtyla, better known as John Paul II.

Poland as a country was not recreated until 1918. This perhaps explains the importance of literature and culture in this country and the aura of those who create it...

It is in this context that the "Polish Poster" must be considered. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the "Polish Poster" has always existed, but when we talk about it as an artistic movement, we are referring to the period 1955–1985. It was one of the high points in the history of world graphic design, one of the essential benchmarks for all young graphic designers of the time. This movement developed with a creativity, a fantasy, an invention, and therefore with a freedom unknown elsewhere...

Talking about creative freedom in a communist country at the time doesn't fit well with the Manichean idea of communism, but the facts are there: this creative freedom existed in Poland and nowhere else.

Attempting to explain the phenomenon, I said that economic censorship was far more restrictive than political censorship. For in this state economy, communication codes escaped commercial logic, and one only had to compare the posters produced for the same film in Warsaw and in the West to understand that the respective artists did not face the same constraints.

One might have assumed that similar movements could develop in other communist countries. This was not the case; Poland was an exception. As always, this movement was born from the encounter of young artists eager to impose their conceptions of the image by adapting to the particularities of the place and the time.

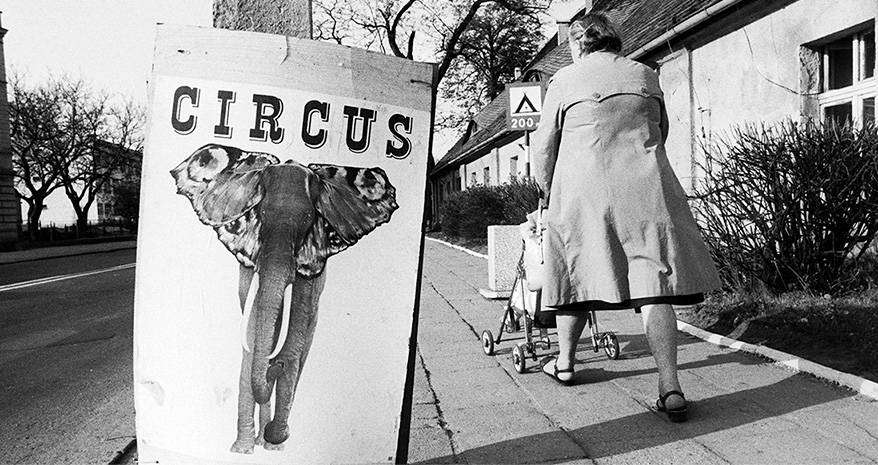

Photo: © Pascal Piskiewicz

this poster by Rafal Olbinski

announces the arrival of a circus.

"The Polish Poster" is therefore the story of this group of artists' "seizure of power" within existing commissions and structures, and of their success in imposing and developing their original communications, outside the conventions respected in the West and the communist aesthetic defined in Moscow...

It is wrongly referred to as a "Polish Poster" style; the only commonality among the artists of this movement was their creative freedom, their ease in breaking free from typographic or graphic codes. This freedom means that forty years later, Tomaszewski's posters remain surprisingly contemporary. Each one developed their own unique language. Jan Lenica's style could not be confused with that of Swierzy, that of Starowieyski with that of Cieslewicz... to name but a few.

Another peculiarity is that the "Polish Poster" was primarily a street phenomenon. While history will only record a dozen or so names, perhaps fewer, it should be noted that all the posters, the good and the bad, reflected this difference, this freedom, this creativity. What struck foreigners arriving in Warsaw was the colorful luxuriance of the posters, contrasting with the grayness of the architecture...

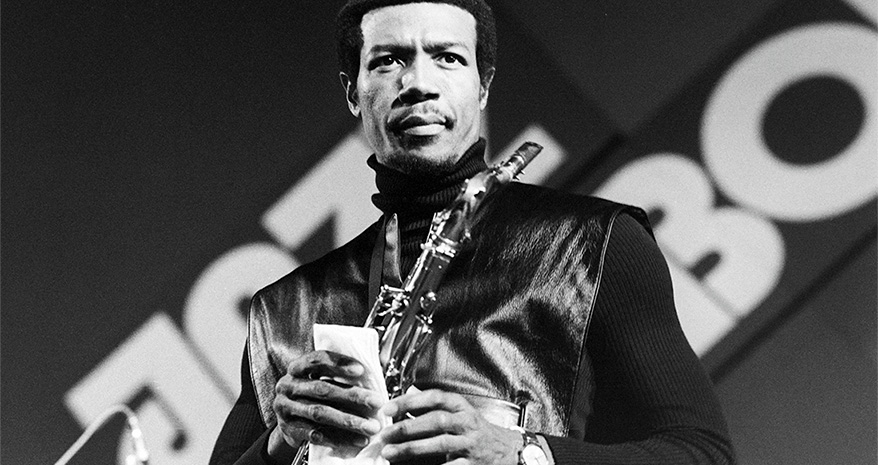

Photo: © Pascal Piskiewicz

It took some time to overcome this general impression and establish a hierarchy of values. The medium, which had become valued, attracted the best creators, establishing competition and emulation. The Polish state, aware of the success of Polish posters worldwide, encouraged the creation of the first international poster biennial, a model for the forty or so similar events that currently exist around the world, as well as the Wilanov Museum, the world's first museum dedicated to contemporary posters.

Like any artistic movement, that of the Polish poster is part of time and space, with its periods of development, plenitude, and slow degeneration, in the very image of the political system whose absurdity heralded its imminent bankruptcy.

When communism imploded, state structures shattered, particularly those of poster production. "The Polish Poster" was already a shadow of its former self. Not that the great artists, now grown old, were not producing quality works, but the inspiration, the utopia had disappeared, and the poster no longer represented anything for young talents. Almost all the major players quietly left... Zamecznik, Mlodozeniec, Lenica, Tomaszewski... they belong to history...

Photo: © Pascal Piskiewicz

Translation: "We will sow in an exemplary manner, thus we will give more bread to the homeland."

Today, "the Polish Poster" and its actors have long since ceased to be references for young graphic designers. History, quite unfairly, will only remember a few names and a few images, always the same ones: "Moore" by Tomaszewskii, "Wozzeck" by Lenica... thus obscuring the others who made this movement real and powerful, unless, on the contrary, this History reveals that Tomaszewski's work escapes the History of Graphic Design to simply enter that of Art, joining in this another emblematic figure of the poster, Henri de Toulouse Lautrec.

Alain Le Quernec

Presentation of the Wilanów museum in warsaw,

the world's first poster museum, inaugurated in June 1968

Français (France)

Français (France)  English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)